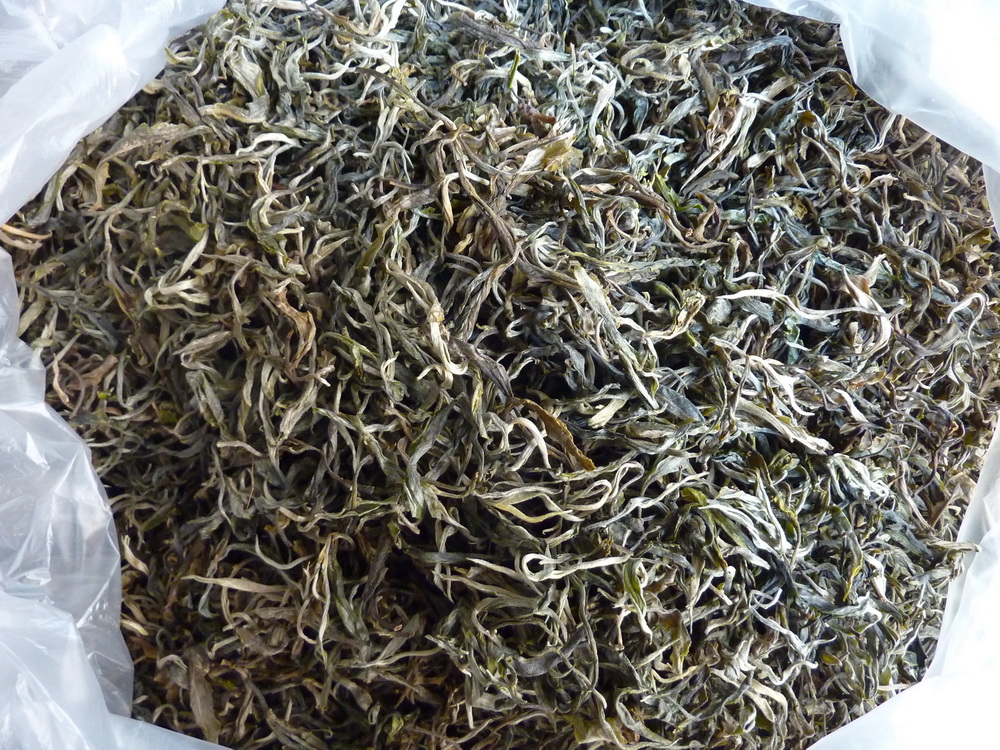

I was talking with a friend, Xiao Zhang, who runs a tea shop near ours. She had just got some Autumn Lao Ban Zhang mao cha for which she already had a probable customer. Whilst sampling the tea I asked her if she would be prepared to tell anyone who asked exactly where the tea was from – i.e. which tea farmer.

An emphatic ‘No’ was the answer, adding that she doubted if anyone locally would be willing to divulge which family or farmers they were getting their tea from.

Here’s the dilemma:

Developing long term relationships with tea farmers has some difficulties: If you have developed or are developing a relationship with a tea farmer, it’s still fragile, even when it may appear quite solid; you have an agreement to purchase a given quantity of, say first flush spring, tea from a given tea farmer but, if someone comes along behind you and offers more money for the same tea, it is tempting for the farmer to take it. In the Xishuangbanna area at least, no-one would be surprised at this kind of incident; tea farmers have gone, in 10 years or so, from more-or-less subsistence living in many cases, to having money to spare. But it is uncertain. It makes sense for them to ‘make hay when the sun shines’. The guy who buys your tea this year, might be gone the next.

The person who offers more money may have fewer requirements than you do and may, if they get the tea, walk away with a lesser quality tea than you might have got from the same farmer. But you still didn’t get the tea and may have to go back to ‘square one’ and find another source of tea that meets your requirements. This often can take considerable time and effort.

I realised in talking with Xiao Zhang that this highlights a fundamental difference in tea producers/suppliers attitudes:

Those sufficiently remote from the region likely need the names of mountain, village, tea farmer, to give credence to their merchandise. They also will understand the appeal that there may be for many westerners in buying a product which has a story behind it: this tea was made by tea farmer X in village Y, etc. even when the veracity of such claims may be hard to prove.

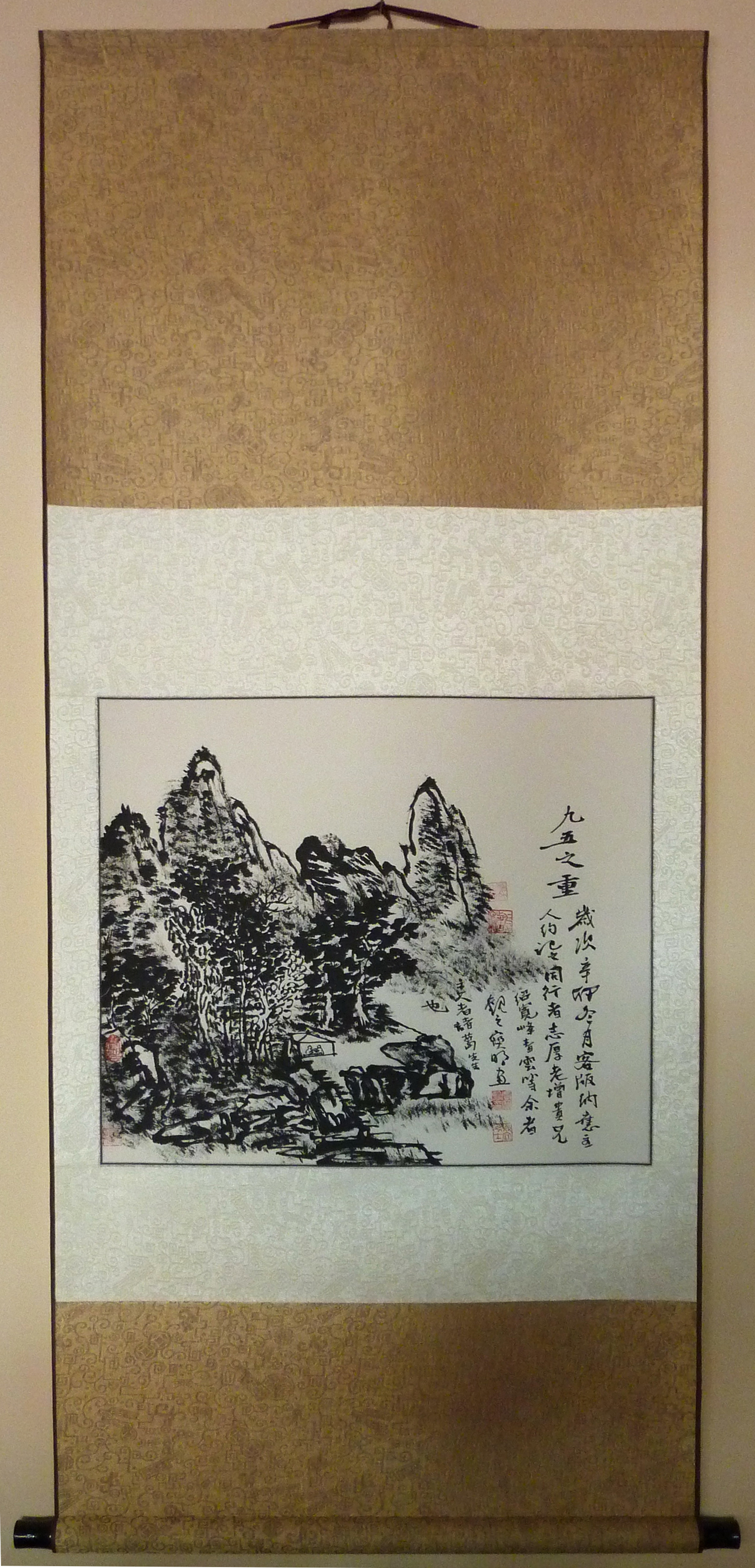

Chinese people generally, particularly here in a small city, in a rather less developed corner of China, are somewhat less removed from the sources of their food. The food supply chain is less of an abstraction than it has become in the west. Imported products are still relatively few, and even fruit and vegetables from neighbouring provinces are often eyed with suspicion. So, whilst local people in Jinghong are well aware of possible food growing practices ( it is quite common to bump into someone you know who will offer some fruit or other saying, “These are from my uncles’ trees, they don’t have any chemicals on them.”), the mantra of provenance for selling foodstuffs is less developed in China,and is less understandable than it is in the west.

Local tea merchants rarely need that credential, and their proximity to the growers means that they at least believe there is a chance that they can keep their relationship with a given tea farmer, and also, that they could lose it.

Suppliers remote from the producing region would, I suspect, rarely imagine that they have anything other than a tenuous link with the producer, so are less worried about others interloping. So, whilst the notion of complete transparency is honourable and justified, in reality, it would, for the time being at least, appear unworkable for the majority of tea merchants and small tea producers near centres of tea production.

There is another problem: we have a steady flow of people who come in the shop with ‘their hands in their pockets’, by which I mean, they do not openly declare their intentions. Sometimes, somewhat after the fact, we might understand that they have come to Xishuangbanna looking for tea, with the idea that they too can go up in the mountains and buy tea, take it home and sell it. If it happens to us, it happens to everybody.

And why not? They’re free to do so. But it would make little sense for anyone involved in the tea business here to give away too much information about their own contacts. The idea of a more open declaration is, for the moment, here in Xishuangbanna at least, rather remote.