I just realised these last few days that it was ten years ago that I made a couple of posts about the old Nan Nuo Shan Tea Factory in Shi Tou Zhai.

(see this post for a brief history of the factory and the man behind it Bai Meng Yu).

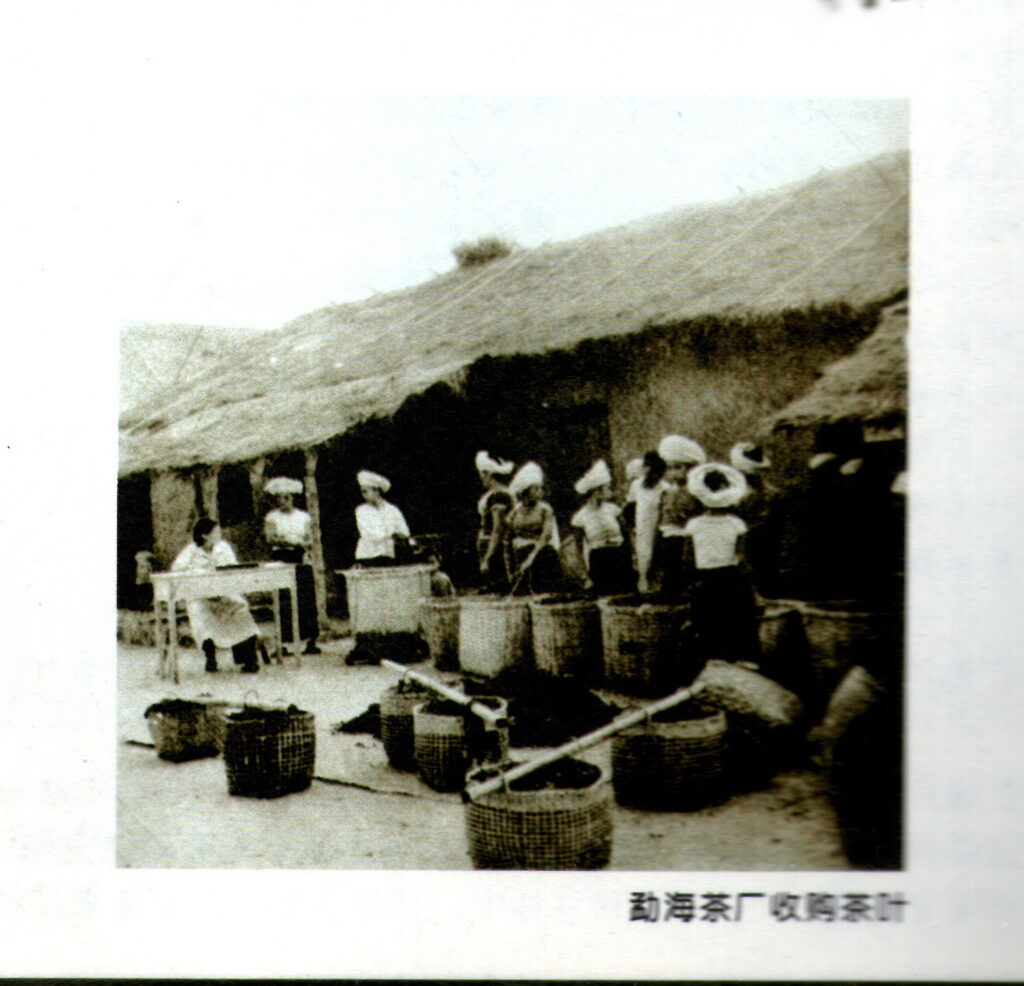

That was in 2011-2012. I was unable to discover much more new information about the history of the factory locally, but I did talk to the people who live in Shi Tou Zhai and had relatives who had worked in the factory. They shared a book they had with me, 普洱茶记/Notes on Puer Cha, and from which I copied a number of pages. I am waiting to confirm who the author was but I believe it to be 雷平阳/Lei Ping Yang. The section of the book on the tea Factory is mostly about the factory from the 1950s onwards. There are a few photos that were interesting but likely from the same era and may not be the actual tea factory.

Within the next couple of years I went a few times to Northern Thailand and, mindful that Bai Liang Cheng (Bai Meng Yu) had gone there after his stay in Myanmar, made a few inquiries to see if any more was known about him there.

Chiang Mai has an interesting, mixed Chinese population who have been there a long time. There are Chao Zhou people who are mostly near the river, centered around Warorot Market, where there’s a small 华人街/hua ren jie/China Town.

Another distinct group of Chinese are the Hui people – Muslims from Yunnan Province – who have been there at least since the late 19th Century. Yunnanese mulateers, who were predominantly Muslim and formed a core element on the trade routes collectively known as ‘茶吗古道‘/ch ma gu dao – Ancient Tea Horse Road in English – made regular dry season trips from Xishuangbanna via Da Luo, Kyaing Tung (Keng Tung) in Myanmar, Chiang Saen on the west bank of the Mekong, Chiang Rai and Chiang Mai, and then on from there on to Burma via Mae Sariang, finally arriving at Moulmein, an important port on the Andaman Sea. (Another possible route headed south from Jinghong to Muang Sing in northern Laos, and from there, after crossing the Mekong somewhere near Chiang Saen, joined the first route to continue to Chiang Rai).

Initially, the traders on the ‘Cha Ma Gu Dao’ were not permitted to cross the Ping River and enter the city proper, so they settled on the east side of the river, in the area that is now known as Wat Ket. Some people have said that this is where the earliest Chiang Mai mosque was established, but that is contradicted by other recorded accounts that place it in the Ban Haw area, south of Wararot Market on the west bank of the river. Ban in Thai means village or home and Haw (sometimes Ho) is a term, with slight derogatory connotations, used in northern Thai for Muslims from Yunnan, that has subsequently come to denote all Yunnanese Chinese irrespective of their religion. The Yunnanese themselves do not use the term.

Key commodities on these long distance trade routes were cotton, tea and opium – an image which has served to haunt them until recent times. But these early settlers had become well integrated into Chiang Mai society by the time the next wave, including KMT fighters, arrived via Burma in the 1950s. They were seen by many, both in Burma and Thailand, as being somewhat wild and lawless.

This latter group had no official documents (and even until quite recently many only had a form of ‘refugee card’ which severely restricted their movements) and their situation in Thailand was precarious. One elderly Hui Man in Chiang Mai described to me once how, at that time, if you were out, walking down the road say, and you saw another person you recognised as being a fellow counryman, you wouldn’t speak or acknowledge them for fear of exposing yourself and being subject to the consequences.

It was into this situation that Bai Meng Yu must have arrived after leaving Nan Nuo Shan in the late 1940s, via a soujourn in Yangon (Rangoon). Knowing that he was Hui meant that the mosque in Chiang Mai was a reasonable place for me to start making some inquiries. One could sense the initial distrust, engendered in part by the history mentioned above, but of course also because of having a strange foreigner coming and asking questions. Being able to speak some ‘Yunnan hua‘ possibly went some way to overcoming that hurdle and, having convinced them I wasn’t a spy or a government agent, I was warmly welcomed.

After a couple of visits I was fortunate enough to meet an uncle of Bai Meng Yu’s granddaughter, who was extremely helpful and friendly. He told me that she had, somewhere in her possession, a number of photographs of the original Nan Nuo Shan Tea Factory. He had a photocopy of a written account that family members had made at the time of Bai Meng Yu’s death, recounting their knowledge of his life and including one photograph of the tea factory in which one could just make out some people, maybe in work clothing, standing in a wooded area, possibly clearing ground or constructing something, but 80’s photocopying in Chiang Mai was surely not what it is today and the photograph was not of much use other than to confirm its existence. His niece (Bai Meng Yu’s granddaughter) was friendly but not that helpful for her own reasons – she was busy with work, had just moved house, didn’t know where everything was, and really? Is anybody interested in that?, etc. etc.

So hopefully, somewhere in Chiang Mai, there are still a set of photos of the old original tea factory waiting to be re-discovered.

On another trip I went to Sha Dian, a now prosperous town in Hong He Prefecture where Bai Meng Yu originally came from and picked up a copy of a publication put out by the local government in 2012 which has a fairly detailed account of the life of Bai Meng Yu, written in 1987. It doesn’t offer much new detail about the tea factory other than to say that he visited India on a trip to purchase equipment for the factory which was subsequently shipped to Burma and from there hauled overland by cart, and then carried by people back to Menghai. It sounds like a slightly more likely scenario than the one of the rolling machine being shipped direct from England since India already had a heavy machinery industry by the end of the 19th Century and a Scot, William Jackson who had gone out to India to work alongside his brother, the then manager of Scottish Assam Tea Co. and had invented a rolling machine some time in the 1870s.*+

On a subsequent visit to Thailand I also made a trip up to Mae Sai, north of Chiang Rai on the Myanmar border where Bai Meng Yu’s sister lived, and where he spent the rest of his life. His gravestone is in a small Muslim section of a cemetery on the south edge of the town

* The earliest tea rolling machines still in use in Darjeeling were manufactured around the 1850s so those, it seems, were shipped from the UK.

+ In a newer edition of Puer Cha Ji by Lei Ping Yang, it states that the machinery, or at least, the rolling machine was shipped from Kolkata (Calcutta) to Yangon (Rangoon), and from there via Kyaing Tung to Da Luo and then Nan Nuo Shan

Previous posts on Bai Meng Yu and Nan Nuo Shan Tea Factory: