Like Picking Money from Trees III

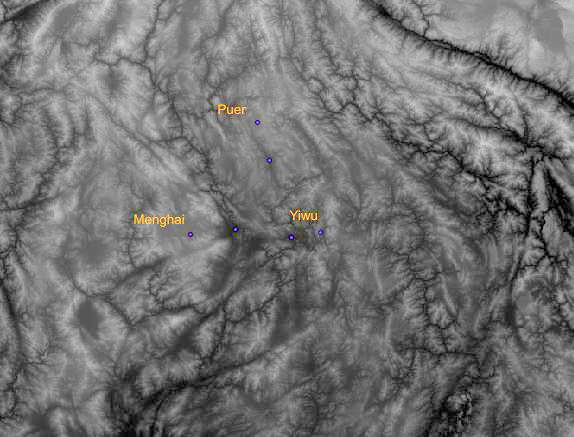

I thought it would be interesting to get a more learned view on the issue of over-picking old tea trees. There’s always plenty of homespun logic available, but less easy to hear from the mouth of an academic, so I decided to get in touch with someone I’ve known for a year or so who’s just that: Professor Chen is on the staff at South China Agricultural University. He’s in the Tea Science Department.

I posed the question to him: When is an old tea tree over-picked?

His reply went pretty much like this:

‘On the problem over-picking tea trees, the main thing is to consider what is ‘appropriate’ picking. The aim of appropriate picking is to ensure a basis of a good, stable yield, to accomplish both ‘regular production’ and to ‘cultivate the tree’ – there is a paradox between the two.

The leaves of camelia sinensis are a vital organ which through the process of photosynthesis give the tree life. To maintain the trees strong vitality it is imperative to maintain stable, abundant foliage. The tree’s total leaf-surface area is an indices of its life-force.

At the same time, tips and young leaves are predominantly picked for tea production; appropriate picking practices can increase yield and also ensure the longevity of the tree. Accordingly, normal tea picking methods are to leave leaves on the tree. Research has clearly shown that if during spring picking a large leaf is left unpicked on the stem and in summer, the ‘fish’ or ‘milk’ leaf is left, it can improve both the quality and yield of the tree two years later.

Old tea tree gardens are somewhat different from plantations. They are less well managed and trees are more easily damaged. If through picking, the tree’s leaf area is reduced too much, i.e. too few leaves, it inevitably leads to early aging of the tree and in extreme cases, its death. Clearly, an appropriate degree of picking is important to maintain old tea tree gardens. Unfortunately, at the moment, there are no scientific research reports on appropriate approaches to harvesting of old tea tree gardens.

He suggested:

1. Old tea trees should not be picked harshly, (that is to say, pick the tree clean – all leaves, irrespective of size – in one go). Each time the tree is picked, a portion of the leaves must be left on the tree.

2. In the spring, during the first and second flush, a large leaf should be left on the stem because June is the time when the tree will lose leaves. In the summer, a ‘milk’ leaf should be left and in autumn, again leave a large leaf.

3. Pick according to the condition of the trees foliage; if old leaves are few, leave more on the tree. If old leaves are plentiful, pick more. In times of drought of course more leaves must be left on the tree. The older the tree, the easier it is to damage its life-force, so it is even more important to leave a proportion of tips and leaves on the tree.

4. When a tree is old it is very easily affected by over-picking. The tree is past its most productive stage and is in a period of decline.

Further research needs to be conducted to understand how over-picking impacts the quality of old tree tea.’

Some people say that the of type approach suggested by professor Chen is not that easy for tea farmers to take on board, and a simpler approach of getting them to re-establish traditional practices in cases where they have been lost would be more effective and would have the same result. However, it’s not all tea farmers who have a lore of tea cultivation in their culture – and certainly not of commercial tea production.

So it’s clear, if not conclusive, that there is, or at the least, there is potential for, a problem. But not so clear how widespread the problem is or how to deal with it. It’s unlikely the regional government, even if it had the will to grasp the issue, would have the ability to police it. So the onus of responsibility is on the farmers and the people who buy their tea.

see here for earlier posts on over-picking tea:

https://horsesmouth.puerist.co/picking-money-trees/

https://horsesmouth.puerist.co/over-picking-tea/

https://horsesmouth.puerist.co/ma-hou-pao/