I’ve been thinking it’s about time to reach some kind of a conclusion on the issue of over-picking old tea trees. But to digress for a moment, I recently remembered these words from a Congolese student of economics I used to know in London:

“les besoins sont beaucoup, mais les ressources sont peut.”

So, putting that to one side for the moment, let’s carry on.

Climate and its impact on Puer Production

We have had a few years of drought conditions which have badly affected yield. Tea farmers are typically reporting a 35-40% drop in yield in 2012 compared with 4 or 5 years ago.

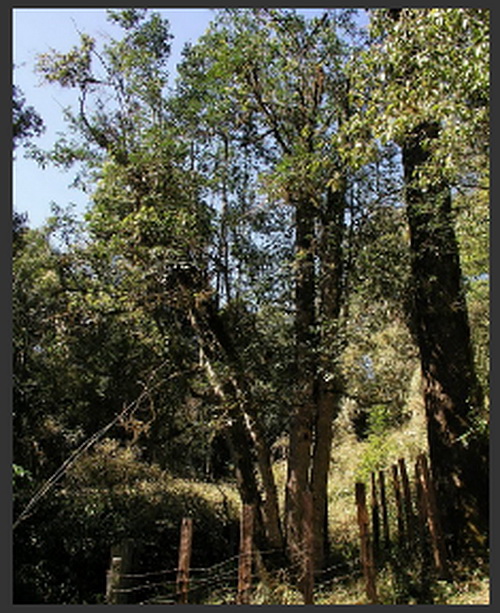

This, admittedly bleak scenario is offset by the topography of Xishuangbanna which creates many micro-climates, thus in some cases, mitigating the impact of localised, if not global climate change.

The factors for the farmer are about income, keeping customers happy and maintaining their (mostly inherited) trees. In the face of the first two, it is easy to see how the last could be relegated in importance in a quest for short term gain.

Not all farmers are necessarily aware of the issues, and may not have a long term view of their own livelihood or the health of their trees, though generally there is an understanding of the nature of the ‘heirloom’ that farmers have inherited and may hope to pass on to their own children.

Greed and the Market

Over-picking is sometimes attributed to the greed of tea farmers. This seems a little disingenuous. From an outsiders point of view, traditional tea farmers houses and lifestyles may look appealing, but I wonder how many people would be willing to take their place? How should tea farmers live? And who should dictate that?

Even as little as a decade ago, tea farmers in Xishuangbanna sold their tea for very low prices: often a few jiao a kilo. Puer tea mao cha was considered more an agricultural product than a high class beverage. Farmers would often travel considerable distances – not easy given the terrain and their limited resources – to try to sell their tea. Some did not even pick tea, apart from a little for their own consumption, until a few years ago, when the Puer ‘boom’ brought a new perception of the resource on their doorsteps. It must have seemed like a little magic to many farmers who suddenly were able to generate significant income without too much outlay, other than their own effort.

Most mountain minorities in Xishuangbanna have been used to living a subsistence lifestyle, so the Puer boom brought about a groundshift in their circumstances. With the cash income that many farmers now have, they are building houses, buying cars, flat screen TVs, computers.

The stories of tea farmers – and rubber farmers too for that matter – are legendary: suddenly coming into a decent amount of money, and then simply going to Moding in Laos (over the border from Mohan) and blowing it all in some mad frenzy at the casino, only to return home with empty pockets and carry on with their hand-to-mouth lifestyle.

So in a way, the fact that more farmers are beginning to have the foresight to put their hard earned money into something solid, like a house, should be seen as positive, even if, from a western point of view, the traditional house the farmer was living in had rather more charm than the concrete construction that has taken its place.

Most farmers houses have rather less stuff in them than other peoples so one can hardly blame them for wanting to acquire more household durables either.

Caveat Emptor

As tea farmers are increasingly exposed to the wider world, their ideas and expectations are changing. It is impossible to oppose or change that – hopefully, in the end, it will be beneficial to all, but one can’t condemn tea farmers for wanting to jump in and get a share of the bunfight that is ‘capitalism with Chinese charateristics’.

Things here are changing quite rapidly, but not all areas of a society or economy develop at an equal pace, and there is surely a process that we most of us know well enough: that ‘things’ do not necessarily equal quality of life, that awareness comes later, mostly after the acquisition of the things that one thought would bring something else into one’s life. But part of that process of acquisition will bring some interesting changes:

A while back, I was with a tea farmer I know in Nan Nuo Shan, who still lives in a traditional wooden has, but one equipped with a number of ‘mod-cons’. He was on the computer using QQ to talk to one of his customers in Shanghai. And this is a guy who left school before his teens without even the chance to learn Mandarin Chinese.

If it’s not already here, the time will probably soon come when someone in America can get online and buy tea straight from a tea farmer in Bulang Shan.

The Needs are Many but the Resources are Few

So back to the opening comment: given recent conditions, a farmer may be faced with a demand that they cannot meet, at the same time seeing a potential near halving of income. Does the tea farmer stand his ground, and resist the pressure/temptation to pick more than is good for the trees, and at the same time tell the buyer that the price has doubled?

Some buyers will go further and offer financial incentives to farmers in order to encourage them to pick more responsibly, but in any case, the buyer walks away with less tea than they were hoping to get for their money and is faced with recouping an investment that the consumer may not be willing bear.

Earlier posts on over-picking are here:

https://horsesmouth.puerist.co/pickin-money-trees-iii/

https://horsesmouth.puerist.co/picking-money-trees/

https://horsesmouth.puerist.co/over-picking-tea/