After comparing two Bulang Peak teas whilst I was in the UK, I thought it might be interesting to bring some of the 2010, UK stored tea back to ‘Banna to compare with some of the same tea that has been stored here in Jinghong.

This therefore, is more an ‘apples with apples’ comparison than the one in the UK which was comparing a 2010 tea stored in the UK for 18 months with a 2011 tea that had been in Jinghong. This time we have the same tea, same batch.

UK cake on left, 'Banna on the right

The first thing is that the difference between the teas is not that obvious. Looking at the colour of the cakes, the broth colour and the dregs, there is some difference to be detected, but it’s not that pronounced.

There is a slight difference in colour between the two cakes – most visible in the tips which are a little darker in the ‘Banna stored tea and in the slightly ‘greener’ hue to the UK stored cake. The top photo (right) is the UK stored cake, the lower one the ‘Banna stored tea. It’s not obvious in the photos here but the ‘Banna tea also looks a little richer, more moist than the UK stored cake, but perhaps I’m just imagining that.

There is a slight difference in colour between the two cakes – most visible in the tips which are a little darker in the ‘Banna stored tea and in the slightly ‘greener’ hue to the UK stored cake. The top photo (right) is the UK stored cake, the lower one the ‘Banna stored tea. It’s not obvious in the photos here but the ‘Banna tea also looks a little richer, more moist than the UK stored cake, but perhaps I’m just imagining that.

The broth also produces marked difference – at least of the kind that I might have anticipated.

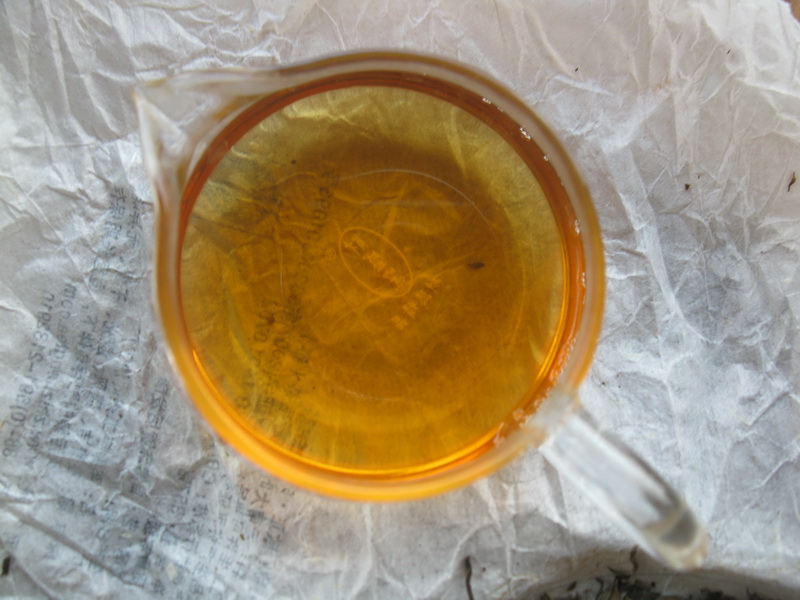

The broth from the first steepings of both teas looks pretty similar in tone.

I started using these two cups – the UK stored tea is on the left – but then realised my mistake as the shape of the cups and their translucency was affecting the appearance of the broth.

So I switched to two identical cups to see how the appearance of the broth was altered. I tried to steep the teas as close to simultaneously as I could in order to minimise any differences caused by oxidation of the broth and steeped the UK stored tea first, so that oxidation would not exaggerate any difference.

As can be seen in the photo above, there is no very obvious difference. Possibly the broth on the left (UK) is a mite lighter than the ‘Banna broth. Both are the third steeping.

Here is the broth from both teas after steeping for 5 minutes. This time the broth on the right (‘Banna) is more noticeably darker, but it’s still not much.

The difference is most clear in the flavour – perhaps as one might have expected. The UK stored cake has kept more of its youthful floral/fruity notes and is very sweet. At the same time it is very slightly more astringent than the ‘Banna stored tea.

The ‘Banna stored tea has lost most of those fruit/floral notes and has started to show hints of something deeper, though as yet, no obvious chen wei. Both teas, when pushed, show a decent kuwei and both resolve quickly to produce a good huigan.

So is there a conclusion?

Of sorts, there is an interim one. It could be that the astringence in the UK stored cake is due to the fact that it has aged more slowly than the ‘Banna tea (and we have forgotten how it was when young) and that with further storage it will diminish. The other possibility, it seems, is that it has been influenced by the dryness of the UK conditions and this has produced the astringence. Only further storage time will tell.