“是薬三分毒 – Medicine is three parts poison“

Background Information

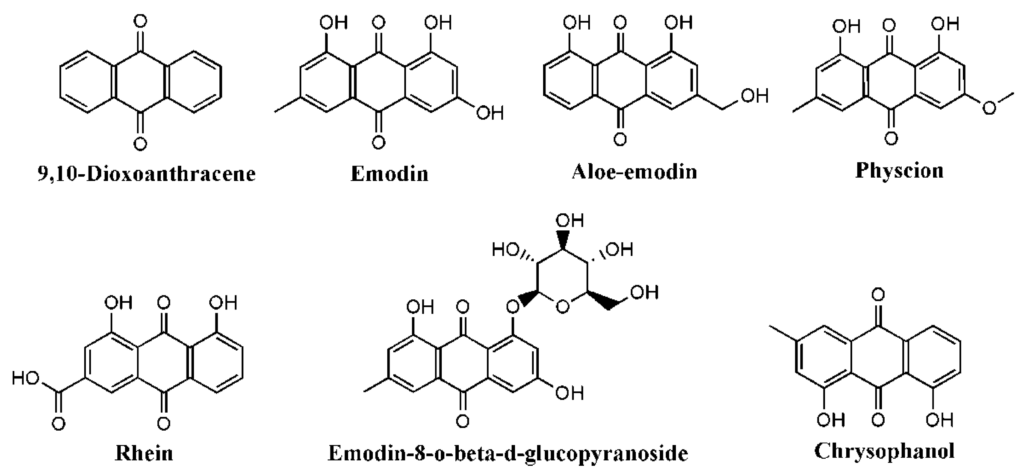

I think by around 2016 or 2017 there started to be talk about a kind of organic (phenolic) compound called anthraquinone (AQ) in tea, etc. As important secondary metabolites, anthraquinones are found in a wide variety of plants, fruits, flowers and fungi, including tea, coffee, senna, rhubarb, aloe, lichens, etc. Fabaceae (pea family), Liliaceae (lily family), Polygonaceae (buckwheat family), and Rhamnaceae families. There are around 200 compounds that are found in plants that belong to this class of compound.

They are common in the human diet and have a variety of biological activities including anticancer, antibacterial, and antioxidant activities that reduce disease risk. Rhubarb (Da Huang/大黄), for example, first documented in Shen Nong’s ‘’Herbal Classic’, the dried roots and rhizomes of Rheum palmatum L., Rheum tanguticum Maxim. ex Balf., Rheum undulatum, or Rheum officinale Bail is one of the most commonly used herbs in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia to “eliminate heat, cool blood, disperse blood stasis” etc.

There are various isomers of AQ but the most important are 9,10 Anthraquinone (Anthracene-9,10 – dione).

The biological activity of anthraquinones depends on the substitution pattern of their hydroxyl groups (OH) on the anthraquinone ring structure. The chemical formula of AQ is C14H8O2.

Uses

Anthraquinones are the main active constituents in a number of herbal remedies and, as mentioned above, Traditional Chinese Medicine, they have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antibacterial, antiviral, anti-osteoporosis, and anti-tumor properties and have a stimulating laxative effects on the large intestine (by increasing fluid in the colon and enhancing peristalsis). At high doses anthraquinone-rich herbs are gastrointestinal irritants, causing symptoms of toxicity.

Apart from its pharmacological uses, AQs are used for dyes, pigments, in chemotherapy drugs, and as a catalyst in paper making. It is also used as a bird repellent. It shows low mammalian toxicity but there are some concerns regarding its potential to bio-accumulate. No serious risks to human health have been reported but it is moderately toxic to birds, most aquatic organisms and earthworms.

Risks

Typical of many plant-based, naturally occurring compounds, AQ has a down side as well as an up. In Chinese there is an expression: ‘是薬三分毒 shi yao san fen du’ or ‘Medicine is three parts poison’. On the one hand having anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-cancer, etc. properties, Anthraquinone is now understood to have potential carcinogenic risks. The maximum residue limit (MRL) of AQ in tea set by the European Union is 0.02 mg/kg. Previously it was 0.01 mg/kg. Japan has not set a specific limit other than to say it ‘must not be detected’. Detectable levels of AQ are rather common, including in Japanese teas.*

Sources in in Tea

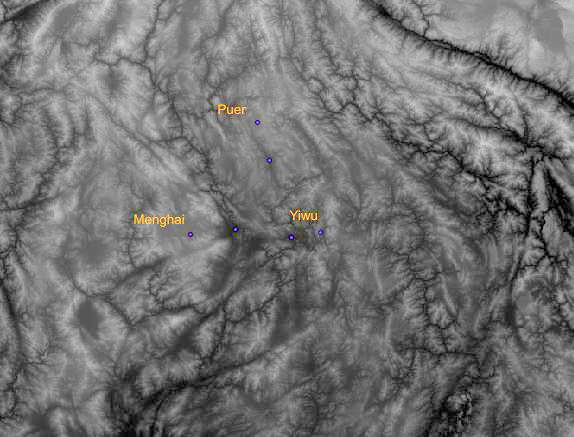

The consensus is that the AQ in tea likely has a few specific origins. The first is environmental, which is a fairly broad definition that might include AQ ‘contamination’ in the air or water from nearby industry, traffic pollution or burning on agricultural land, forest fires, etc. This could therefor affect the fresh leaves and also the dried leaves through the drying process if the tea is sun dried.

The second possibility is in the ‘fixing/sha qing‘ process of tea making or in the drying process if tea, like black tea, is oven dried. Research has found that the AQ content of tea processed in different ways can vary considerably.

Tea Processing

Processing of tea. Most tea is ‘fixed’ using some form of heat, either hand fried in a wok or in a mechanised process – a machine driven rotating drum – with some kind of heat source underneath. Also as part of the wilting step in black tea processing, heated air coming from furnaces that are used for drying tea can be sent up to wilting troughs toward the end of the withering process.

Some research has found that ‘coal’ fired fixing compared with fixing using an electric heat source in green tea processing, saw increased AQ levels of 4.3 to 23.9 times, far exceeding the EU’s 0.02 mg/kg, The same trend was observed in Wulong tea processing using coal heat. The steps with direct contact between tea leaves and fumes, such as fixation and drying, are considered as the main steps of AQ production in tea processing. The levels of AQ increased with the rising contact time, suggesting that high levels of AQ pollutant in tea may be derived from the fumes caused by coal/char/charcoal or other organic matter combustion.

It was also found that different types of tea, with their different processing methods, produced different levels of AQ.

“9,10-Anthraquinone is produced by a reaction between benzoquinone and crotonaldehyde. On the other hand, emodin and physcion are two hydroxyanthraquinones produced by fungi and have been found in microbial fermented teas, including Pu-erh and Fuzhuan brick teas. The ingestion of hydroxyanthraquinones have been shown to have both beneficial and deleterious effects. The safety dosage range and the time of administration required for a satisfactory benefit/risk balance of both anthraquinones are still unknown.”

Research on Humans

Firstly, to date, there is no proof of a connection between AQ and cancer in tea drinking humans.

In a US National Library of Medicine report on rats published in 2012 they stated:

“No studies of human cancer were identified that evaluated exposure to anthraquinone per se;

however, a series of publications on dye and resin workers in the USA, who were exposed to anthraquinone, was available. These workers were potentially exposed to anthraquinone during its production or its use to manufacture anthraquinone intermediates. Effect estimates were reported for subjects who worked in anthraquinone production areas, but they were also exposed to other chemicals, and effects specific for exposure to anthraquinone were not analysed. A study of substituted anthraquinone dyestuff workers in Scotland (United Kingdom) was also available; however, it was unclear whether anthraquinone was used to produce the intermediates in this study”

The same report stated:

”Currently, there is insufficient evidence that human exposure to AQ causes cancer. A case–control study by Barbone et al. (Citation1992) observed a 2.5-fold increased risk of lung cancer in subjects from AQ dye-producing areas. However, there is no direct evidence from this study that AQ causes cancer. In addition, Wei et al. (Citation2010) found that DNA oxidative damage in the human body is linked to AQ exposure. The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified AQ as a possible carcinogen to humans (Group 2B) (International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Citation2013). AQ is commonly found in the natural environment and has been detected in the air (Albinet et al., Citation2006; Cautreels et al., Citation1977), water (Akiyama et al., Citation1980; Q. Liu et al., Citation2021; Meijers & Leer, Citation1976) and soil (Rodgers-Vieira et al., Citation2015), as well as in herbs, spices, coffee, tea and other foods (Díaz-Galiano et al., Citation2021). Apart from these, AQ also occurs naturally in the seeds used to produce cassia gum (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2010). Humans can be exposed to AQ through the above pathways”

Research on Rats

The National Library of Medicine report describes research done on rats where AQ was administered orally:

“Groups of 50 male and 50 female F344/N rats were fed diets containing 469, 938 or 1875 ppm anthraquinone for 105 weeks. Further groups of 60 males and 60 females received 0 or 3750 ppm anthraquinone for the same period. These dietary concentrations resulted in average daily doses of approximately 20, 45, 90 and 180 and 25, 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg bw anthraquinone for males and females in the 469-, 938-, 1875- and 3750-ppm groups, respectively. At 2 years, animals in the highest-dose group weighed less than those in the control group.”

After 2 years rats in all groups had ‘significant levels of adenoma or carcinoma, ….. papillomas’ affecting the kidney and bladder.

In another study from 2022, “Acute and Subchronic Oral Toxicity of Anthraquinone in Sprague Dawley Rats” research was conducted on groups of 10 male and 10 female rats by giving them doses of AQ (gravage) of 0, 1.36, 5.44, 21.76, and 174.08 mg/kg bw, 7 days a week for 90 days followed by a recovery period of 28 days. They concluded that the ‘no observed adverse effect level’ (NOAEL) for anthraquinone in rats was 1.36 mg/kg bw and the ‘lowest observed adverse effect level’ (LOAEL) was 5.44 mg/kg bw.

Research on Tea

In a report “Anthraquinone in Chinese tea: concentration and health risk assessment” published in 2024 it states:

“The concentration levels of AQ in tea varied by different types of tea, different packaging types, different sale spots and different tea-producing areas. The results of the deterministic assessment show that the health risks associated with daily exposure to AQ via tea consumption are low in different populations in China. For the general population, the mean daily exposure of AQ via tea consumption was (2.50 × 10−4) µg/kg body weight (BW), 0.0037% of the acceptable daily intake of AQ (6.8 µg/kg BW). In the different sex-age groups, the highest mean daily exposure of AQ via tea consumption was found in the male group aged ≥ 60 years, which was (2.84 × 10−4) µg/kg BW. The high consumer exposure (95th percentile, P95) was found in the female group aged ≥ 60 years, which was (9.36 × 10−4) µg/kg BW. Green tea is the main type of tea with AQ exposure by Chinese tea consumers.“

They also say:

“Our study found that the total detection rate of AQ in 1573 tea samples was 60.97%, indicating that AQ contamination was prevalent in the Chinese commercial tea samples. The mean concentration was 0.0170 mg/kg, which did not exceed the MRLs set by the EU. Among the different types of tea, this study confirmed the findings of Yuan et al. (Citation2020) and He et al. (Citation2019), who found that dark tea had the highest over-standard rate of all types of tea. These results are most likely related to the unique production process of dark tea-pile fermentation, which is more complicated than other types of tea (Yuan et al., Citation2020). Some studies have shown that the concentration of chemicals in dark tea may also be related to its high maturity (Yang et al., Citation2012) and aging time (Liang et al., Citation2022; Liang et al., Citation2023). In addition, what is surprising is that the mean concentration of AQ in white tea in this study was higher than in other types of tea, this result can be explained by the following fact that domestic sales of white tea in China are small. Therefore, for a result with statistically significant differences in the detection rate, over-standard rate and concentration, the white tea sample collected in this study was too small“

Furthermore:

“From a producing and processing perspective, studies have demonstrated that smoke from wood fire or coal may be one of the sources of AQ contamination in tea. AQ can also be a process contaminant, the chemical reactions between crotonaldehyde and hydroquinone during tea processing also may be a potential pathway for the endogenous formation of AQ in tea“.

“The results of the exposure assessment showed that the mean daily exposure and consumers at the P95th percentile daily exposure of AQ via tea consumption in the general population were (2.50 × 10−4) µg/kg bw and (8.41 × 10−4) µg/kg bw, respectively. Furthermore, our study found that the health risks associated with exposure to AQ via tea consumption are extremely low for the general population and the different sex-age groups“.

Some sums

Let’s say a lab rat weighs 445g (F344/N) and is fed 90mg/kg body-weight of AQ (taking the figures from above) then the daily dose would be 40mg/day. If the rat was given only 20mg/kg-bw daily (the lowest dosage in the research), the daily dose would be 8.9mg daily.

If we relate that to a 60kg human:

i) If we calculate what the equivalent dosage for a human being would be, using the lowest dosage rate (20mg/kg/day), it would result in the consumption of 2696mg per day of AQ.

X=20 x 60/0.445 = 2696mg per day

ii) At the higher rate in the example (90mg/kg/day) it would result in the consumption of 12134mg of AQ per day.

Let’s imagine those levels of AQ are consumed entirely from tea – on the assumption that all the anthraquinone in the tea would be transferred to the broth and was then consumed – taking the EU MRL of 0.02mg/kg:

At the lowest dosage, it would look like this:

2696/0.02 = 134,800kg. i.e. 134 metric tons. That’s every day for two years in order to get to the same equivalent level of intake.

If we take the figures from the second research paper, using the NOAEL of 1.36mg/kg bw:

For a 60kg human, the ‘no observed adverse effect level’ would be 81.6mg daily. Using our previous example of tea containing 0.02mg of AQ per kg of tea, one would need to consume 4 tons of tea daily:

X=1.36 x 60 = 81.6mg per day

So 81.6/0.02 = 4080kg. That’s four tons.

Using the ‘acceptable daily AQ intake of 6.8 µg/kg BW’ (for which I have to acknowledge a caveat since I don’t know how it was derived at) for a 60kg human, that would calculate out as 6.8×60/0.02, we get 8,160kg. Eight tons.

You get the idea..

To look at it from another angle – if one drank 10 different teas (each of 8g all with the same 0.02mg/kg limit) , 80g of tea all together, every day, one would imbibe:

80/1000 x 0.02 = 0.0016mg of AQ per day. That would be 0.008 % of the minimum dosage used in the first experiment, or 0.12% of the NOAEL limit referred to in the second research paper. Or, if we take the ‘acceptable daily intake’ referred to above we get: 0.0016/6.8 = 0.0235%.

That’s not to dismiss the potential risks of excessive consumption of anything. And not to doubt that there are risks involved, but it’s important to keep it in perspective.

And remember too that this 0.02mg/kg MRL (originally 0.01mg/kg), was set by the EU, which has still failed to include glyphosate in any standard testing protocol. A conspiracy theorist might, over a cup of tea, be forgiven for wondering whether, if anthraquinone was made by Monsanto, we would even be considering it.

Conclusions

For anyone concerned about buying selling tea within the EU this might be an issue as it may be that some teas would not pass EU testing requirements. Personally, I am rather more concerned to avoid agro-chemical residues. By that I mean that, whilst most definitely doing my best to avoid tea that won’t meet EU criteria, I do not consider AQ levels to be a priority. If a tea is good and chemical free, yet may still have some detected level of AQ, I may well go ahead with it anyway.

With tea making, there are limits to what one can do as there are many factors which are beyond one’s control: if people in Myanmar or Thailand, or over the other side of the mountain, are burning rice stubble during tea season there’s not too much one can do about it. Most contemporary hand frying set-ups have a wall between the side of the stove where the wok is, and where the tea is fried, and the side where the wood is added to the fire. As long as chimneys are well made – tall enough with good draw – there is limited chance of smoke from the burning wood getting into the tea. Making sure frying woks are regularly cleaned and rinsed during the tea frying process (to avoid any buildup of residues) and hands/gloves are clean are practical step that may help minimise the potential for AQ in the tea. Machine frying using a rolling drum (滚筒/gun tong) or a thing called a ‘chao tian guo‘/朝天锅 (think of something like a cement mixer with the revolving drum made of cast iron on better models, or otherwise steel). In earlier times gun tong were wood fired but now, like chao tian guo are more likely to be heated by electricity or bottled gas, but the result is not the same as hand frying in a wok, so they are often used for larger quantities of tea and ‘small tree tea’, etc. but are still not often used for premium old or ancient tree teas.