I have recently had cause to hang out with two different Chens – a Chinese name something akin to the English Smith. One in Hekai, on the edge of the Bulang Mountains, and the other from Guangdong who sources tea from the Six Famous Tea Mountains area.

Chen No1 is based in He Kai. I went up there a few weeks ago and then accompanied him to Lao Ban Zhang where he got 30 kg of fresh leaves. The cost of fresh tou chun leaves in Ban Zhang this year was anything from a little over 400 to over 600 RMB/kg, and this Spring, just over 4 kg of fresh leaves was making a kilo of mao cha.

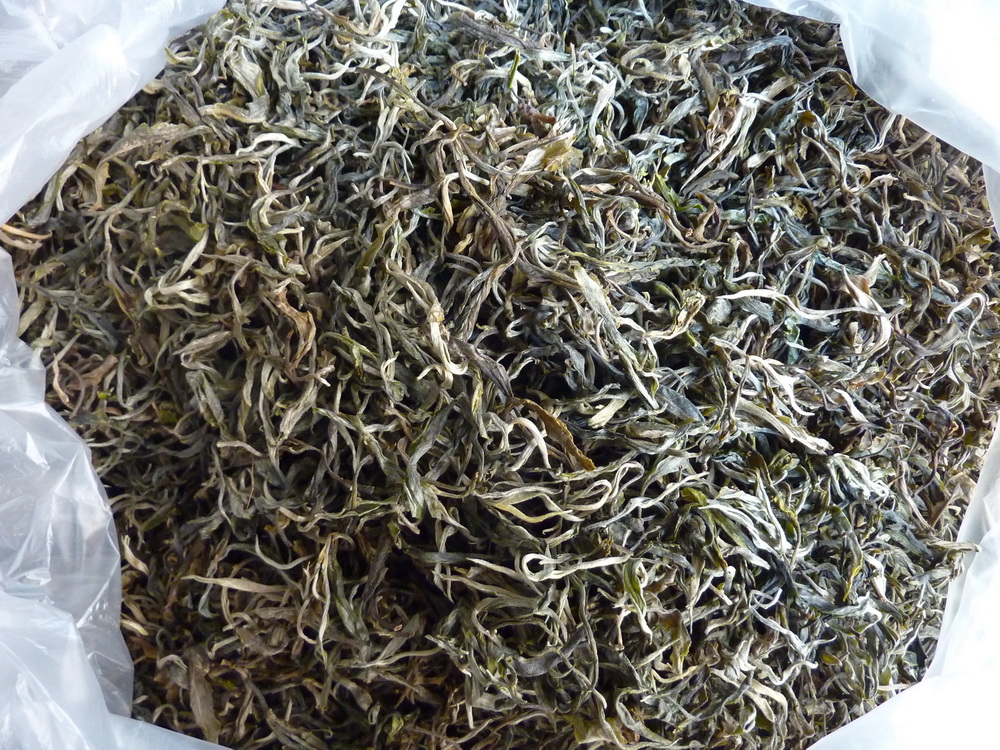

We got back to his place with the tea around mid-day and spread it out to wilt for a while. He started frying tea later in the afternoon and continued till almost midnight, putting the tea out to dry the next morning, which is normal practice.

His sha qing approach is a little different from some tea makers as he tends to fry the tea for considerably longer than is typical, and then rolls it for a relatively short period of time. When tea is heaped in the pan during frying in the fashion described above, it is locally described as ‘dui de‘ or piled.

He Kai Chen left his tea to wilt for a fair time even though the weather’s very dry – although it had been raining a little at night when I was there – (one reason for wilting, apart from allowing the moisture content in the leaves to drop, is to allow it to even out, so that there is a more uniform amount of moisture throughout the leaf – from tip to stem. If this is not done, it’s easy to burn the leaves).

Typical tea frying woks in the Bulang Shan/Hekai/Ban Zhang area are set flat on a brick oven. Initially, the tea leaves are kept moving in the pan which must be done to stop the leaves from burning and to produce an even roast. As the tea is roasted, the heat is allowed to drop a little and the tea moved less. After frying for a while – maybe as much as 15 minutes – during which time the tea is turned and shaken out repeatedly (this allows some of the heat to disperse), the process slows down and the tea is turned and then piled in the centre of the wok and left for a minute or so. This process is repeated many times.

Chen Lao Ban then takes the tea out of the wok and leaves it on a tray for several minutes – again piled as opposed to spread out, which is the more common practice.

Making tea in this way, he then machine rolls it in an old electric roller with a wooden drum and tray, but only for a few minutes. The result is a tea that is very fragrant, has good body, with a light clear broth, little astringence and good hou yun.

When He Kai Chen makes tea completely by hand, as he did with some of the Ban Zhang tea, he does not follow this method, and has a more typical approach to frying and rolling.

Across the other side of Xishuangbanna, a few weeks later, I was in Ge Deng and bumped into another Chen. Chen Lao Ban is from Guangdong where he sells tea. He spends quite a lot of time in ‘Banna and has been sourcing/making tea in the Liu Da Cha Shan area for 5 or 6 years. He has set up a few small chu zhe suowhere he both processes fresh leaves and collects some mao cha.

Guangdong Chen has had a wok made according to his requirements: the wok is also set flat on the oven in a manner similar to Bulang Shan woks, but it’s a fair bit higher. One only has to fry tea for a few minutes in a wok in say, Nan Nuo Shan, to realise how important the height is! Most Aini people are relatively short, and build their ovens accordingly, so this can be back breaking for anyone taller.

His approach to tea making is almost as far from Hekai Chen’s as Ge Deng is from Hekai. The wilting time is probably about the same – somewhere between 3 and 5 hours, but his approach to sha qing is quite different. Tea Urchin referred to this style as ‘medium rare’. I like that description. I think a lot of people I know here would say it was ‘sha bu tou‘ – not fried enough, but Guangdong Chen (and lots of other people in Guangdong) seem to like tea with this kind of flavour; a little less smooth feeling in the mouth than is typical, a fair bit of astringency, and not much obvious fragrance; either in the leaf or the cup. And virtually none of the retro-olfactory aromas that He Kai Chen produces.

Chen Lao Ban says that when the tea is stored (in Guangdong), the astringence mellows, though I have to say, that in my (limited) experience of drinking tea in Guangdong, even after several years, tea is often still markedly ‘apre’. He Kai Chen also says his tea ages well. I have had some which was 3-4 years old which was reminiscent of a rather older tea; very smooth, good hou yunand a pleasant chen wei.

What is most interesting in all this is that Puer making methods, within a broader understanding of the process, can vary considerably. There is not necessarily any ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way of doing things – and I suspect there never was – although it is easy to find people who will swear by one particular approach.