When one thinks of Gong Ting (Tribute Tea) one first thinks of Man Song and when one thinks of places of historical importance related to Puer tea in Xishuangbanna, one perhaps first thinks of Yibang or Yiwu, or maybe Gedeng, but Mang Zhi has its share too.

Man Ya is below Hong Tu Po and the quickest way to get up there is from the Xiang Ming road.

Once across the bridge, it’s quite a quick journey up to Man Ya where the ancient tea tree gardens are. Like many places here, the original village no longer exists and the inhabitants have all moved further down the mountain.

One reason that this has happened is because of a lack of water, or the need for it outstrips the resources. Another is simply convenience. Sometimes villages have also been moved by the authorities.

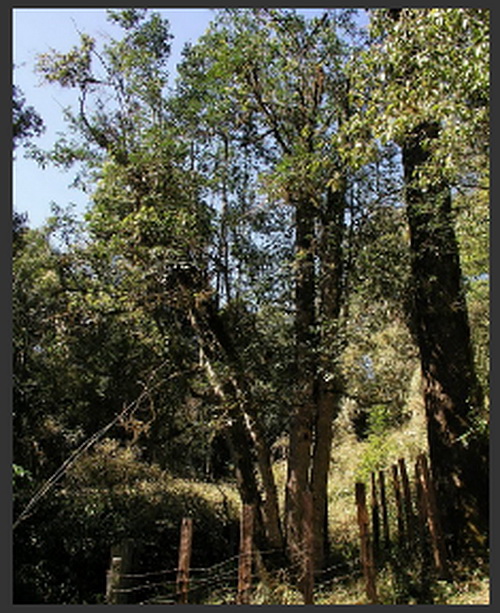

These trees, known by the villagers as Tian An Men provide a fitting entrance into the area where the gardens are. As with many places, the gardens are a mixed bag with some xiao shu near areas of older da shu and gu shu, but the general feeling is still good.

Most villagers make tea in or on the edge of the tea gardens, while several sell the fresh leaves they have picked to someone else from the village to process.

Many of the trees are similar to those in other Liu Da Cha Shan areas, but a few are significant, like the one below with a girth of 60 or 70cm.

The gardens have good ground cover with plenty of ‘za cao’ or weeds.

Lost in the undergrowth are a couple of tombstones which appear to be maybe Ming Dynasty and look like they were for government officials. One has been defaced, it seems by…. well you know the story. The other is still in relatively good condition.

It is said that tea from these gardens was also Tribute Tea – tea that was reserved for emperors or government officials.