HM had gone to Menghai to organise some pressings the other day when our neighbour Lao Feng, dropped by. He somehow seems to me like a kindred spirit and I enjoy drinking tea with him.

He came in, and having said he didn’t mind what tea we drank, I found a cake of Bang Wai on the shelf that I didn’t remember ever tasting (in fact I’m pretty sure now I never tried it). We made a number of 150gram cakes last spring from a range of tea mountains: He Kai, Jing Mai, Naka, Luo Shui Dong, Ding Jia Zhai, Mang Zhi, Bing Dao, Xi gui, Bang Wai, Ban Ma. All in small quantities. At most we had a set or two of each: 10 or 20 Kg.

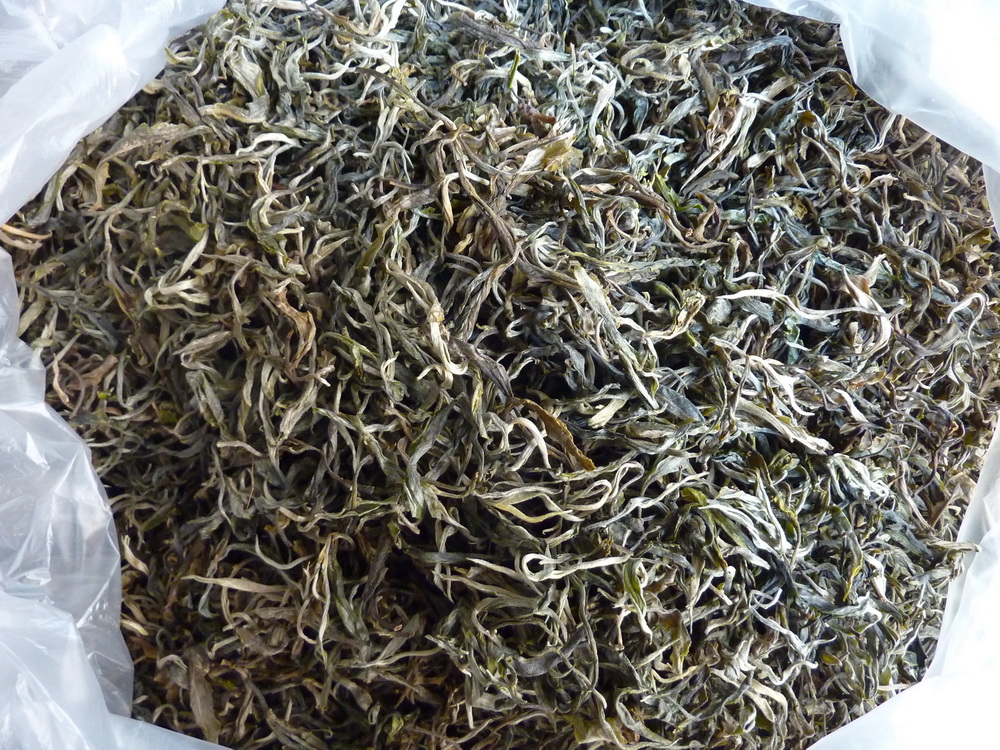

The Bang Wai tea looks good, though there’s nothing particularly notable from the outwards appearance of the leaves.

Bang Wai 250 gram cake from Spring 2012

The broth is exceptionally clean. Early steepings produced a pale yellow broth with virtually no astringency and a hint of bitterness that lingered on the upper palate. Later steepings produced a pleasing rich gold broth.

Bang Wai 2011 Spring sheng Puerh broth

The tea has lost any ??? ‘qing chou wei‘ that it had and has yet to develop any noticeable ?? ‘chen wei’. Initial impressions are of tobacco and old books, hints of leather.

By the end of the first couple of steepings, I could feel a warmth creeping up my occiput and face. The tea feels quite penetrating and both Lao Feng and I begin to feel the effects in the palms of our hands: a warmth and energy that makes the skin slightly moist. I can also feel it around my upper arms and shoulders.

Sharing tea experiences with Lao Feng is enjoyable, not least because he is very interested in the energetics of tea. Not from a scientific, Newtonian perspective, but from an experiential one. We concur that one sign of a good tea is how much it penetrates energetically. He comments that ‘some teas are powerful as they enter, and some powerful as they come out.’ It’s certainly so with this tea. The rukou had no clear sweetness or xiang qi – but there is a powerful, floral sweetness that floats up through the throat from somewhere deeper inside and penetrates the nasal cavity.

Bang Wai leaves after 5 or 6 steepings

We become very still as we focus inward to better perceive/appreciate the process. Another friend comes by and quietly joins in. He too, quickly notices the effects this tea produces. He says he feels it first penetrates to the 丹田 ‘dan tian’ and then spreads out to the hands.

We recall a Chinese sage – no one can remember their name – who said about only drinking seven cups of tea. With this tea, it seems to be true. The experience is quite powerful and after 5 or six steeping we’re all happy to pause and enjoy the lingering sweetness and aroma that continues to float up in the throat for another 40 minutes or so.